Chakawak learned early on that rights and freedoms must be fought for. She grew up in Panjshir as the daughter of a well-known lawyer and women's rights activist: "People said my mother was an infidel. Some even wanted to kill her."

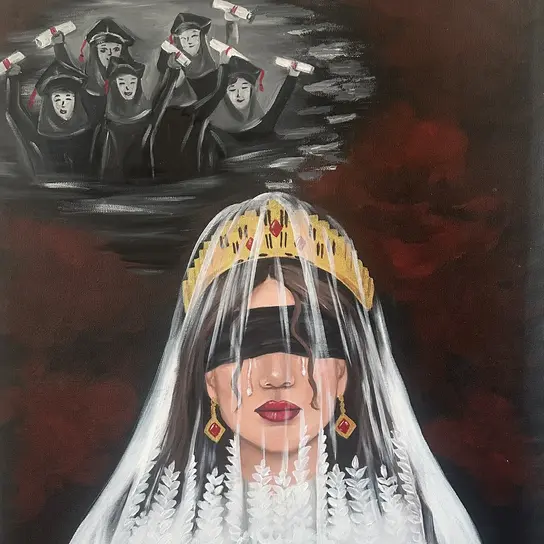

Violence also reigned at home. Her drug-addicted father abused her and her children. "He wanted to forbid my mother from working and take me out of school. And when I was twelve, he wanted me to get married." For her mother, divorce was a huge risk. Nevertheless, she used her network to finally separate and move out with her children. She became Chakawak's role model. "My mother showed me that you can fight. And you must." Chakawak became an outstanding student, interested in poetry and philosophy, became a youth representative for her province in Kabul, and planned to go to university.

Then came the day that changed everything. She was 15, it was the last day of her final exams. "The headmaster came into the classroom and said: 'The Taliban have taken over Afghanistan.'"

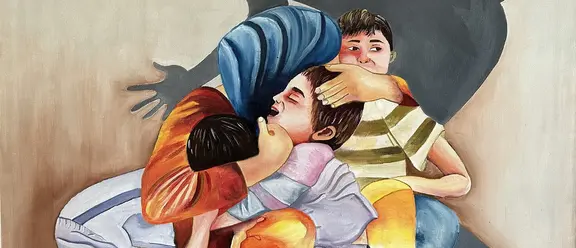

Fighting broke out in Panjshir – her mother organized protests, and Chakawak joined them. Many fellow protesters were arrested, tortured, and some were murdered. The Taliban were also searching for her mother. Her father, who had joined the Taliban earlier, searched for Chakawak and arranged her forced marriage to a high-ranking Taliban fighter. When they found out, the family fled to Kabul.

At 16, Chakawak had to learn to live underground. "I was constantly afraid that the Taliban would find us. Or my father." Her mother fought tirelessly, trying to bring her and her brother to safety. Their only hope was her cooperation with a German human rights organization.

But the requirements of the federal resettlement program seemed almost insurmountable: "It took weeks until we had gathered evidence of persecution and all the other documents. Any contact with the outside world was life-threatening. How are you supposed to prove you're being persecuted while on the run? That my father wants me to marry a Taliban member?"

Meanwhile, the Taliban confiscated her house, threatened relatives, arrested and tortured colleagues, and her mother received threatening phone calls.

But the application process was opaque, lengthy, and complicated. After several months, they finally received confirmation from the responsible German authority, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF). Now they still had to go through the visa procedures at the German embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan.

Once again, they faced enormous obstacles: “How do we get to Pakistan? Where are we supposed to get thousands of dollars for visas? And how do we travel without a male escort?” The German authorities refused to assist single women with their departure – they insisted on abiding by Taliban law, which forbade women from traveling without a male guardian. They borrowed the money from an uncle. “At the border, we had to pretend we belonged to another family. I was so afraid they would recognize us.”

But Pakistan offered no protection either. The father could bring her back by force at any time. At the German embassy, the visa process began: renewed checks, renewed interviews. Then came the waiting – for months.

"Some had their acceptance promises revoked without explanation. What would happen if our case were also rejected? Then the Taliban will kill us."

Then came the message from the embassy: Without the father's permission for the children to leave the country – no visas . "I thought that was it. That I would never be free. That he had power over me again." Her mother was summoned and explained once more that her husband was a danger. But the embassy stood firm.

The mother took a big risk and contacted community leaders in her hometown. They were lucky; old friends helped. The father was told the family was already in Germany but needed a certificate for health insurance. He charged for the approval—but he gave it.

Then came the relief: The flight time was announced, and they were taken to the airport. "But until just before boarding, the German embassy refused to hand over our passports. People were pulled out of the queue by the federal police. We were terrified that we wouldn't be allowed on board either. Our nerves were on edge until the very last second."

Today, Chakawak is 19 years old and lives in Germany. Her fear for her friends in Afghanistan remains: "Most of my friends were forced into marriage. They have nothing left. No rights, no life. I hear about suicides more and more often."

She is also troubled by the fear that Germany will deport Afghans again. But the Taliban and her father are far away now, and Chakawak is dreaming again: "I want to write poetry again. Study astrophysics. Be free."